Why Adrian?

Whatever your background, Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà can provide you with the skills and experience you need to realize your dreams.

Why Adrian?

Whatever your background, Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà can provide you with the skills and experience you need to realize your dreams.

Undergraduate Studies

We offer an undergraduate program of study that’s small enough to be personal

Graduate Studies

Pursuing your dream career starts with the next phase of your education. When you enroll in graduate school at Áù¾ÅÉ«ÌÃ, you’re beginning more than advanced training in your field; you’re accelerating your professional journey.

Posted Thursday, August 29, 2024

Author: Mickey Alvarado

Representing the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) as a Doping Control Officer during the Olympics in Paris was serious business for Tina Claiborne, Ph.D., Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà Professor and Director of Graduate Athletic Training, having to account for the drug testing of many world-class competitors, including medal-winning swimming, golf, track cycling and weightlifting athletes.

Claiborne wouldn’t say exactly who she tested due to protocol, but she was in the presence of Olympic greatness while performing her duties.

“Just imagine the most famous athletes in the world,” Claiborne said.

A few of the highlights from venues Claiborne was assigned to included Katie Ledecky winning her ninth career Olympic gold medal to become the most decorated female Olympian ever from the U.S.A., while Jennifer Valente, the first American woman to have won gold in an Olympic track cycling event, picked up two more in Paris. Olivia Reeves won the first U.S.A. weightlifting Olympic gold medal in the past 24 years.

Claiborne said there were athletes who tested positive prior to the start of the games and subsequently banned from competing, the first was in Judo.

“The goal was to test every competitor. At events, every medalist got tested, plus a couple more in line who didn’t make the podium,” she said.

Many times, results do not become official until after the ceremonies, and testers learn along with the general public, if one of the medalists tested positive.

“It’s not like we’re on the inside track because there’s a lot that has to happen,” Claiborne said. “Once the samples are collected, they are sent to an accredited lab, analyzed, and potentially re-analyzed. It is not unusual for further investigation and arbitration to occur prior to any imposed penalties. Once everything is finalized, positive tests become public knowledge.”

It was the first time Claiborne worked at the Olympics.

“It was the most unique experience, I think, that I’ll ever have,” she said.

Claiborne got her start in drug testing while in graduate school at the University of Toledo. Her boss was a Doping Control Officer and employed her as a witnessing chaperone for USADA.

“When we’d go test athletes of the opposite gender, he’d have to bring somebody of the same gender to witness the urine sample. In graduate school, I would do anything for a few extra bucks, so I started my drug testing career there.” Claiborne joked.

Although she has worked for USADA for more than 20 years, this was the first time she applied for Summer Olympic duties. There were 600 International Doping Control Officer nominees worldwide, and she was one of nine selected from the United States. Claiborne believed that the final Paris 2024 anti-doping team consisted of over 250 Doping Control Officers.

Traveling to Paris for the Olympic games on someone else’s dime would be a wonderful vacation for the average tourist, but for Claiborne it was mainly work. There wasn’t a lot of spectating for the Doping Control Officers.

“Before we started working, I was fortunate to be able to pop my head out and see a little bit of competition,” she said. “Probably the most special moments I saw were not necessarily when U.S. athletes won. It was when French athletes would win because the stadiums, the crowds would just erupt. The patriotism that every spectator and athlete felt for their country was really moving in a lot of ways. I was out there when the most famous French swimmer, Leon Marchand, won his first gold and you could just feel the energy, it was like nothing else.”

She had plenty of time to check out the scenery on her commute to the various venues as it took at least an hour each way on public transportation. Her experiences with French cuisine came from the stadiums she worked in.

“It was not a vacation, I promise. It was hard work, but it was one of the most rewarding experiences in my professional life,” Claiborne said. “I would apply to go again. The winter Olympics are in Italy, so that would be really neat, and, of course, the summer Olympics are going to be in L.A., so the US Anti-Doping Agency is probably going to have a big role in organizing that.”

She said the best part of the trip to Paris was meeting and working with people from all over the world. There were doping control officers from at least 45 other countries.

“That was most special,” she said. “It would have been great working for Team U.S.A., but I’m actually glad that I was in the job I was in because I was able to interact with people from everywhere.”

While at the Olympics, she ran into a couple of old friends/co-workers including Keenan Robinson, a 2002 Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà graduate, who is the Director of Sports Medicine and Science for U.S.A. Swimming.

She also ran into Ben Towne, a former Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà athletic trainer who was Robinson’s clinical instructor, who is working full-time as an athletic trainer for the U.S.A. Bobsled Team.

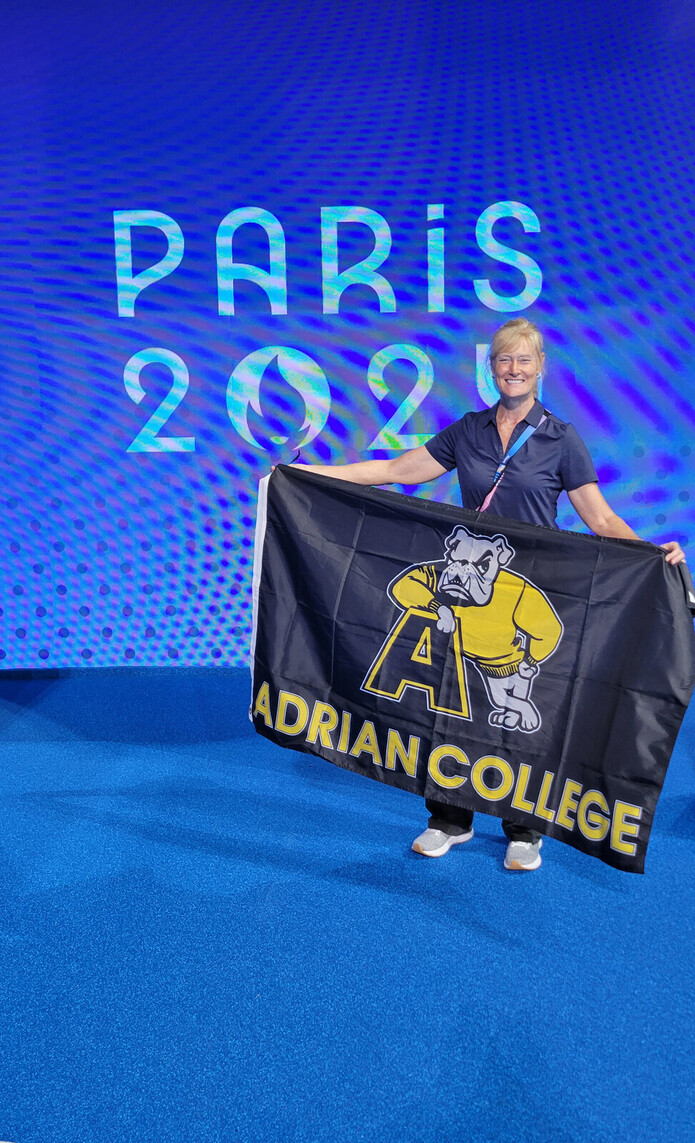

Claiborne was able to get out a couple of days to explore Paris and check out the main tourist locations, usually with an Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà Bulldog flag in hand.

“I’m obviously very proud of Áù¾ÅÉ«ÌÃ,” she said. “I’m proud of our athletic training program and the institution overall. It was really fun to catch up with people who had an Áù¾ÅÉ«Ìà connection, and show that we are, in fact, on the world stage.”